The dividing line between patriotism and nationalism can sometimes become blurred. For the resettled Bhutanese this is particularly relevant when marking the National Day of Bhutan on 17th of December.

According to American journalist and author Sydney J Harris, the difference between patriotism and nationalism “is that the patriot is proud of his country for what it does, and the nationalist is proud of his country no matter what it does.”

Following the National Day celebrations in 2018 and 2019 in Australia by a group of resettled Bhutanese, a number of questions found expression among members of the resettled community worldwide. Should former citizens, who have been persecuted, disenfranchised and expelled, celebrate the national day of their country of origin? Should an individual or group attempt to represent thousands who might not share the same ideas? Do they actually have any such representative capacity? Should the history of the persecution be forgotten in the pretext of idolizing the “nation” of one’s birth? Not all the questions raised have been answered with the thoroughness each deserves.

Social media engagement on the matter among community members has been mostly superficial and, at times, vicious. Critics of the national day events, in view of the history of persecution, and the expulsion of citizens by the Druk regime, find the celebrations patronizing. The advocates interpret it as an expression of “nationalism” towards the country “that gave us our identity”.

Two issues are clear. The event organizers are within their rights to do what they have, as long as the law of concerned jurisdiction permits, and no individual or group can claim to represent all the interests of the Bhutanese diaspora.

A contentious issue deriving from the 111th national day celebration was a suggestion that the resettled Bhutanese forget the history of persecution. Subsequently, the Bhutan News Service carried an article titled “Should the History of Persecution be Forgotten?” that dispelled the notion that forgetting was a virtue or a pathway towards a solution. Drawing appropriate evidence from history, transitional jurisprudence and the science of victimology, the article argued that truth was the “primary basis for normalizing post-persecution situations” and that “forgetting initiatives” posed “serious contradiction” that impeded “the normalization process, severely impairing the possibility of healing.” “Throughout history”, the article noted, “it was the persecutor who advanced forgetting initiatives” as opposed to a member of the persecuted community.

The forgetting initiative coming from a member of the persecuted community, in the present case, is indeed strange, especially when justice has not even been initiated to victims of persecution. In contrast, perpetrators of violation in Bhutan have been rewarded when transitional justice requires lustration of abusers.

The 112th event abandoned the forgetting proposition. This was a welcome change. So, what remains to be considered about marking Bhutan National Day?

A significant concern that surprises members of the diaspora is the overall impression the said national day events generated. To an innocent observer oblivious to Bhutan’s distinction of persecution and refugee generation, the messaging is unequivocal. In spite of that history, these events present the Druk nation as an ideal hermit Kingdom capable of no wrong. To an observer familiar with Jigme Y Thinley or Tshering Tobgay (former prime ministers of Bhutan) presenting their case to international audiences, these events evoke a déjà vu feeling. The portrayal of multi-culturalism presented during the events struggles to conceal the Drukpa brand of ‘nationalistic’ fervor that takes over the occasion.

Some specific examples are helpful. The event was a platform to introduce Bhutan as a proponent of Gross National Happiness (GNH). It is a matter of fact and one of public knowledge that the happiness principle in the GNH form, is Bhutan’s brainchild. Domestically, GNH is a directive principle under article 9(2) of Bhutan’s constitution which is meant to guide all other policies/laws. Internationally, however, the Bhutanese government has used GNH as a defense mechanism to deflect and diffuse questions or criticisms about the regime’s human rights credentials.

In one such attempt in New York, Jigme Thinley is quoted to have said that even street dogs smile in Bhutan, the birthplace of GNH. The general message the government intends to convey is that “we are a GNH nation, a ‘hermit kingdom,’ deeply rooted in Buddhist values and utterly incapable of any malfeasance.”

Placed at 95th among a list of 156 countries in 2019 in the happiness index, it is hard to vouch how happy the Bhutanese actually are. But the principle has indeed been an effective safeguard to frustrate the expelled citizen’s claim of persecution.

From a government perspective, the tactic is understandable. The claim, however, appears bizarre when a former refugee declares that “we are the happiest country,” projecting among the gullible audience that wellbeing alone is what the Druk regime is interested in.

Why would a former refugee or a member of the persecuted community present the expelling nation as an epitome of happiness? Is it a case of idyllic altruism? Is it one of total amnesia? Is it a case of mere expediency? Or, is it an innocent expression of “nationalism”? What else can the motivation be for a member of the persecuted community, who suffered years of deprivation, to absolve a perpetrating government so liberally? Whatever the motivation, whether it is innocent, ignorant or intended, the damage is done.

Bill Shorten, a member of the Australian parliament (MP), while ‘celebrating’ the five generations of Bhutanese monarchs, characterizes the fourth king as being “pious” in his later years and credits him for constituting a harmonious country. No one denies the MP the freedom to celebrate whosoever he desires. But the facts belie his statements. How do piety and harmony, attributes the MP ascribes to the monarch, exist in the same person who was responsible for persecution and eviction of one-sixth of the country’s citizens?

The fact that Shorten was addressing a group, among others, of refugees/former refugees who suffered immense deprivation because of the action of the very person the MP was pleased to extol, aggravates the irony.

Critical of the rise of “authoritarian leadership” in China, Russia and America, and lamenting Brexit (the process of Britain leaving the European Union), the MP portrays the Druk regime as an infallible Shangri-La. We have nothing to believe that he was ignorant of the facts on Bhutan, for, he knew and did mention about Bhutanese refugees. These inherent inconsistencies not only speak volumes about the integrity of the speaker, but also warn of the damage powerful people can inflict by distorting the history of the powerless.

The Bhutanese Australian leading the event chose to “pay tribute to His Majesty the king” for the “achievements” attained thus far, rather than remind the honorable MP, and those gathered, that there were Bhutanese refugees in Australia who were not products of piety or harmony.

The truth is that the Druk regime is guilty of a series of wrongs. Thousands of Bhutanese refugees continue to suffer in Nepal’s refugee camps. While the international community, including Australia, has resettled a majority of them, the state of their origin continues to subvert its international responsibility. Political prisoners continue to suffer in Bhutan’s prisons, incarcerated for decades without trials or hearings. Many citizens, disenfranchised and properties nationalized, of whom some served long prison terms without trials, languish in Southern Bhutanese villages.

The reinstatement of citizenship, a Royal prerogative, is exercised less on reason than on whims. As the southern Bhutanese helplessly face an aggressive state-sponsored cultural onslaught under the “one nation, one people” national juggernaut, the resettled Bhutanese encounter what Ashwin Sanghi, describes as “the problem of distory,” or distortion of history.

Many in the diaspora suffer a “mysterious mental health disorder” that Ken Thompson, a US-based psychiatrist calls “Nepali-Bhutanese Syndrome.” This ailment, Thompson says is “a result of “trauma suffered in Bhutan, from being forced to leave their homes to torture by the government,” among others. Listing a complete catalogue of sufferings in the Bhutanese community is not feasible here.

In such circumstances, painting an all-is-well picture and presenting the Druk regime as a pious reservoir of happiness is tantamount to distorting the truth and brutally muzzling the voice of the weak.

In Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History, Michel-Rolph Trouillot presents us with a deft analysis of how power operates in order to manufacture the history of the powerful while stifling that of the powerless. The analysis comes with a prophetic warning that the first history begins outside of academia. Trouillot states that “long before average citizens read the historians who set the standards of the day for colleagues and students, they access history through celebrations, site and museum visits, movies, national holidays,” among others. Notice his use of the word “celebrations”.

Here, in these national day celebrations, history is being distorted to the advantage of the ruler and powerful, just as Trouillot warned. That the actors in the events were a powerful lot, was evident. The “power’ manifested in the flamboyance at display amidst the wining and dining, the social echelon of most attendees in the jamboree and their ability to disseminate the message the way they intended.

As future national day events are celebrated, all conscientious and inquiring minds must appreciate that the exclusive ethnic nationalism advanced by the Druk regime is diametrically opposed to the inclusive constitutional patriotism offered by Australia. No amount of affectation can conceal the reality. History, as it generally does, shall judge the candid, the complacent and also the complicit.

Truth matters. It matters to the powerful too. Sooner than later, truth alone will matter.

Celebrating the National Day need not be soiled by falsities. The founder of modern Bhutan, Sir Ugyen Wangchuk, left his descendent with a Bhutan of 47,000 square kilometers. Present Bhutan has been mysteriously reduced to about 38,000 square kilometers. The much subdued “tsa wa sum” Bhutanese, unlike the Nepalese citizens (who made their government accountable for breach of boundary) can’t question the ruler. Even at the time of writing this piece, there are reports of Bhutanese territories being infringed. If the national day celebration is an honest expression of “territorial nationalism” the loss of Bhutanese territory, and the threat thereof, are the most relevant issues to highlight in the forthcoming event. That is patriotism.

Thousands of expelled citizens await dignified repatriation. Unknown numbers of citizens are condemned to infinite incarceration for believing in liberty and inherent rights of human beings. Many in southern Bhutan are arbitrarily demoted to the status of residents following disenfranchisement and seizure of their property. If the national day celebration is a sincere expression of “constitutional nationalism,” these will be the most relevant issues to raise. That is patriotism.

To be proud, no matter what a ruler does is an expression of feudal allegiance, rather than of patriotism. A national day celebration deserves better.

Multiculturalism, pluralism and constitutional patriotism constitute the core of Australian national values. As Australians gather to “celebrate” the exclusive Drukpa nationalism of “One nation, one people,” they must introspect on the moral question confronting them. The former Bhutanese acting on the strength of their new found freedom and liberty, too, must do some soul searching. Would these former Bhutanese be even present here today, had the Australian government declared “all is well in Bhutan” and rejected resettlement? This is a moral question history will raise for a long time to come.

__

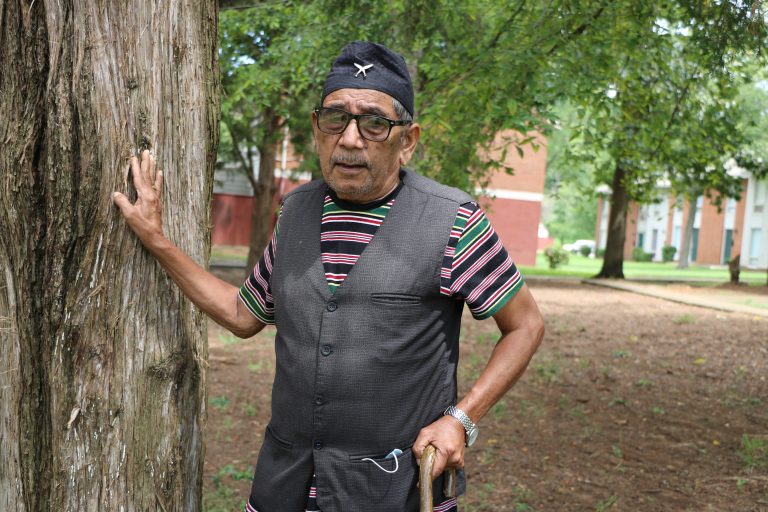

The author, an alumnus of Georgetown University School of Law, is a former Bhutanese refugee and currently lives in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.