One morning in September 1990 there was a firm knock on my door. It was an old buddy of mine from the village. He looked excited and came straight to the point.

‘Hello Lok Nath,’ he said. ‘Let’s join the andolan for democracy and human rights, it is our day.’ He was referring to the protests being organized by the Bhutan People’s Party in Sibsoo Sub-Division and across southern Bhutan. I felt an urgency in his tone and couldn’t refuse.

Two of my older sons had already left home to join the movement and the villages were no longer safe places for them. We were supposed to join the protest from India where plans had been made in consultation with our Indian counterparts and local sympathisers. I couldn’t resist the urge to join my fellow villagers and dressed for the occasion, and a week before the demonstration, I left my wife and two younger children behind to join my peers across the border.

The invitation to join was hard to resist, and the decision was all mine. It seemed that everyone felt the same except for those who decided to side with the authorities for financial and other government gain. Their activities were to make the situation worse in the days after the protest.

I think September 30, 1990 was the big day, when the BPP organized the peaceful protest in Samchi District. The Sibso Sub-Division headquarters was close to the Indian border and it was easier to march across the border than travel straight from the villages through difficult terrain.

We marched shouting ‘hail democracy, hail human rights, guarantee fundamental rights, long live our king’. Those chants reverberated above us and seemed to shake the ground beneath our feet. Such positive vibes made us feel that our actions would bring results.

Despite the erosion of our cultural identity in the south, we still had deep respect for the fourth King. We staged a two-day ‘dharna’ (silent protest) in front of the Dungpa’s Office (Sub-Division HQ), taking turns in groups. The action had been well coordinated across the southern districts. We submitted our 14-point demands for democracy and human rights and continued our sit-in hoping to get a fair hearing.

There were claims that people had joined the movement after being threatened, but nobody in my group had experienced threats. We joined either because our friends were involved or because we were inspired to campaign for positive change. We felt an urgency to do something to correct the course of history which seemed to be going in the wrong direction for the southern Bhutanese or Lhotshampas.

But events took a turn for the worse. The local authorities mobilized the Bhutan Army and the police mounted a surprise attack on the second day of our protest. We ran for cover to the nearby paddyfield where I and my second son were arrested along with around 150 others.

We were held in Sibso Junior High School for a few days before being transferred to Samchi Jail. Some of us were then released after making individual statements, including my second son. I was not one of those released but I certainly didn’t want to jeopardize my relationship with my friends and run away with a pretext.

We spent about 17 months in Samchi Jail where we were treated fairly well and fed regularly, although we were forced to undertake some physical labor. But then the real nightmare began. We were transferred to face the horrors of Chemgang jail, near capital Thimphu, where conditions were inhumane.

The inmates were separated into age groups and I was in the older group. I heard that the younger prisoners were physically and mentally tortured while the older ones were subjected to harsh physical labor. The cells were dark and cold and we had little clothing to keep us warm. Some officers clearly exceeded their authority and found their own ways to add to our discomfort.

A month-long confinement in Chemgang jail felt like years. I shudder to think about some of the horrible things they did to the younger prisoners such as peeing on them and giving them metal to eat instead of food. Yet during all those agonies we felt the King would intervene and give us justice, we all believed him to be just and fair.

My family back in the village was harassed by the security forces on a daily basis as they claimed to be looking for my sons and myself. Although they knew I was in jail they pretended not to. I thought their action was aimed at unleashing psychological terror on my family in order to encourage them to leave the country. The security forces would ransack my house, leave it in tatters and return after a few days to do the same. I think it was highly unethical for the King to order them to do that. But despite that he was still held in high esteem.

In mid 1992 I was released from Chemgang Jail and headed home to Sibsoo to join my family. Some of my friends in the village advised me to submit an appeal to stay in the country, but when I visited Dungpa’s office (Sub-Division Head), my plea was turned down. I was instead forced to sign the voluntary migration form (VMF) stating that I was leaving the country willingly and happily. I returned home with a dejected heart and started preparing for our departure from Bhutan.

A few days later we organized a religious ritual (puran) and, with a heavy heart, left the country travelling first towards India and from there to Nepal where we joined other refugees.

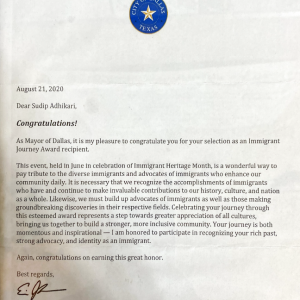

Much is said about the hardship of refugee life but it was better than being in jail in Bhutan. It was the start of our long journey to a new life in the West. I eventually arrived in the United States in 2009, and I am happy to be here as a naturalized citizen. Being accepted means a lot to people like me when no one accepted us.

After about 10 years in Atlanta, Georgia, my family decided to move to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. My health is now deteriorating day by day. Without my children providing care on a daily basis I couldn’t do even the simple things any more.

It’s amazing that so much of the cultural identity I shared with Bhutan, Nepal and India didn’t help me remain there. The United States is truly a great country for people like me. Despite the language barriers I have faced, life is much better here than in Bhutan or in the refugee camp, and being in a big country has its own advantages. I am so grateful to my new country and I have no mental baggage left in which to complain about the past I have lost.